Pregnancy Risks of ACE Inhibitors & ARBs and Safer Alternatives

Oct, 26 2025

Pregnancy Antihypertensive Switch Calculator

Switching Antihypertensives During Pregnancy

Based on ACOG, ACC, and Medsafe guidelines, this tool helps calculate appropriate dosing when switching from ACE inhibitors or ARBs to pregnancy-safe alternatives. All recommended medications are classified as Pregnancy Category C or better.

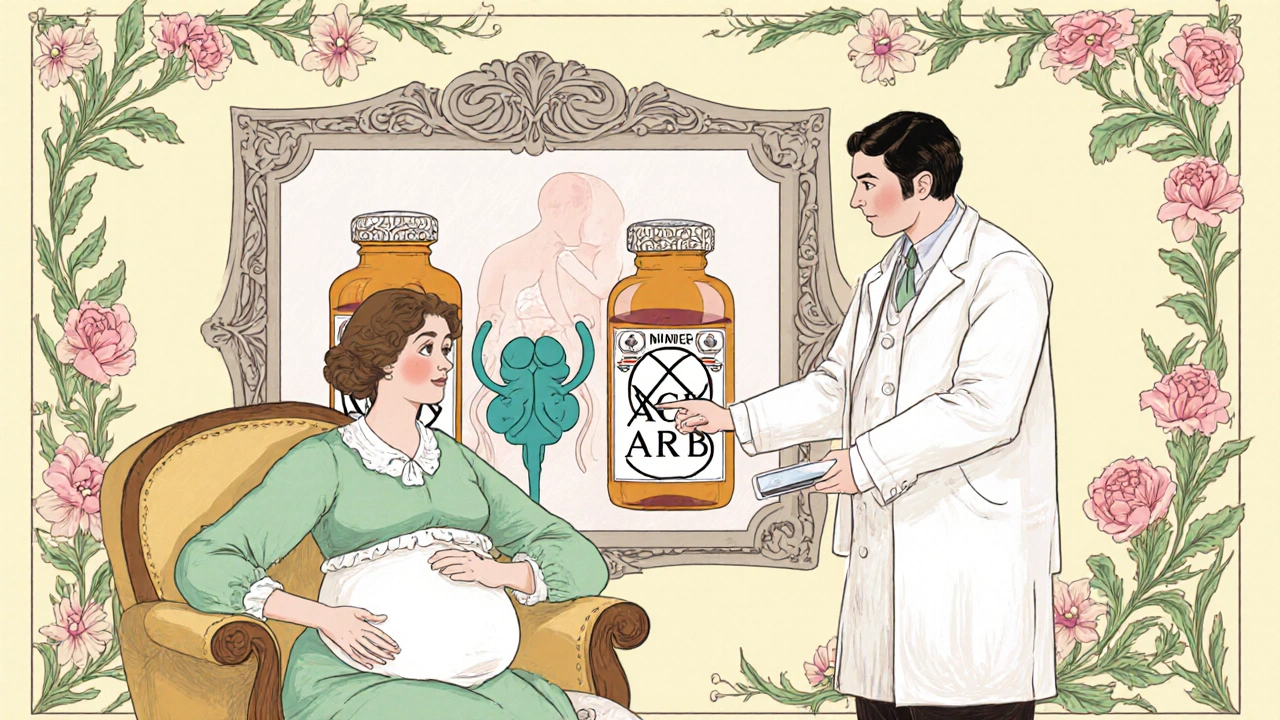

When it comes to high blood pressure in pregnancy, ACE inhibitors are a class of antihypertensive drugs that block the renin‑angiotensin‑aldosterone system (RAAS), a hormonal cascade that regulates blood pressure and fluid balance.ARBs (angiotensin II receptor blockers) work downstream by preventing angiotensin II from binding to its receptor. Both drug families are lifesavers for many adults, but they turn into fetal danger zones the moment a pregnancy is confirmed. This article explains why, lays out the real‑world evidence, and gives you a clear roadmap for switching to safer alternatives.

Why ACE inhibitors and ARBs are off‑limits in pregnancy

RAAS isn’t just a blood‑pressure lever for the mother; it’s also essential for the developing kidney, ureteric buds, and amniotic fluid production in the fetus. Interrupting this system can cause:

- Oligohydramnios (low amniotic‑fluid volume)

- Fetal renal hypoplasia or outright renal failure

- Skull ossification defects

- Severe hypotension and hyperkalaemia in the newborn

- Increased risk of miscarriage and preterm delivery

Because the fetus depends on a fully functional RAAS, any drug that blocks it is considered teratogenic. The FDA placed both classes in Pregnancy Category D long before the 2015 labeling overhaul, and today every major obstetric guideline brands them as “absolutely contraindicated.”

What the data actually say

Several high‑quality studies have quantified the danger:

- Moretti et al. (2011) found a 25.4% miscarriage rate in women exposed to ACE inhibitors or ARBs versus 12.3% in disease‑matched controls.

- The same cohort reported average birth‑weight drops of 350 g and gestational‑age reductions of 1.8 weeks.

- Buawangpong’s 2020 meta‑analysis confirmed a statistically significant rise in adverse outcomes even when exposure was limited to the first trimester.

- Buoyed by FDA’s 2021 adverse‑event reports, about 1.2% of pregnancies in hypertensive women still involve inadvertent ACE‑i/ARB exposure.

While some early reports suggested no increase in major structural malformations, the consensus now is that the cumulative risks-especially renal and amniotic complications-outweigh any potential benefit.

ACE inhibitors vs. ARBs: Is one worse?

Both drug families are forbidden, but ARBs appear to carry a slightly higher fetal‑risk signal. The American Heart Association’s 2012 review labeled the outcome "poorer following prenatal exposure to ARBs" and highlighted more frequent reports of severe oligohydramnios. In practice, clinicians treat them the same way: stop immediately and replace with a pregnancy‑safe agent.

Safer antihypertensives for pregnant patients

Guidelines from ACOG, the American College of Cardiology, and Medsafe all converge on three first‑line options:

- Labetalol (a combined alpha‑ and beta‑blocker with minimal fetal side‑effects)

- Methyldopa (a centrally acting alpha‑2 agonist with the longest safety record in pregnancy)

- Nifedipine (a calcium‑channel blocker used as second‑line therapy)

Labetalol is usually the go‑to because it can be titrated quickly and covers both heart‑rate and vascular resistance. Methyldopa works well for chronic management, though it may cause sedation. Nifedipine is handy for acute spikes but should be avoided in women with pre‑existing cardiac dysfunction.

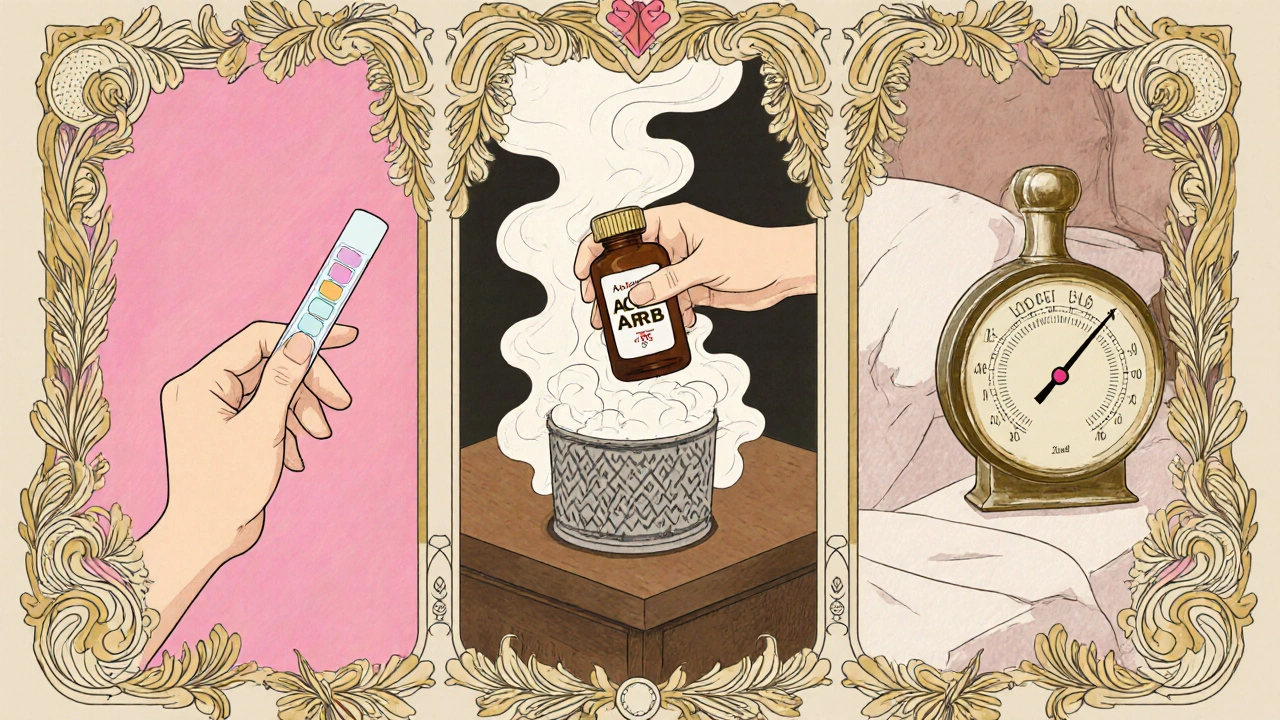

Switching protocols: A practical step‑by‑step guide

- Confirm pregnancy with a quantitative hCG test.

- Stop the ACE inhibitor or ARB immediately - no taper needed.

- Initiate the chosen alternative within 24 hours.

- Labetalol: start 100 mg PO twice daily, increase by 100 mg every 2‑3 days to a max of 2,400 mg/day.

- Methyldopa: start 250 mg PO twice daily, increase by 250 mg every 2‑3 days to a max of 3 g/day.

- Nifedipine (extended‑release): start 30 mg PO once daily, may increase to 90 mg/day.

- Monitor blood pressure at least twice daily; target <140/90 mmHg unless there is severe pre‑eclampsia.

- Check renal function and electrolytes at baseline and after 1 week of the new drug.

- Provide contraception counseling for any woman of child‑bearing potential who will need antihypertensive therapy again.

These steps align with Medsafe’s 2024 advisory and ACOG’s Practice Bulletin No. 234.

Pre‑conception counseling: Avoiding the mistake before it happens

Women planning a pregnancy should have a medication review early. The American College of Cardiology (2023) recommends:

- Ask every hypertensive patient about pregnancy intentions.

- If pregnancy is planned, switch from ACE‑i/ARB to a safe alternative at least three months before conception.

- Document the switch in the medical record and provide written information about fetal risks.

Clear communication cuts the 1.2% error rate that still shows up in FDA adverse‑event data.

Quick reference checklist

| Medication | Class | Pregnancy Category (US) | Typical Use | Key Fetal Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE inhibitors | Renin‑Angiotensin‑Aldosterone System blocker | D | Chronic hypertension, heart failure | Renal dysplasia, oligohydramnios, fetal death |

| ARBs | Angiotensin II receptor blocker | D | Hypertension, diabetic nephropathy | More severe oligohydramnios, renal failure |

| Labetalol | Alpha‑beta blocker | B | First‑line hypertension in pregnancy | Minimal; occasional fetal bradycardia |

| Methyldopa | Central alpha‑2 agonist | B | Chronic hypertension, pre‑eclampsia prophylaxis | Very low; possible sedation |

| Nifedipine | Calcium‑channel blocker | C | Acute BP spikes, severe hypertension | Rare; watch for fetal tachycardia |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a woman take an ACE inhibitor during the first trimester?

Current guidelines consider any exposure at any stage unsafe. Even first‑trimester use raises the chance of miscarriage and low birth weight, so discontinuation is recommended as soon as pregnancy is suspected.

What should I do if I find out I’m pregnant while on an ARB?

Stop the ARB immediately and start a pregnancy‑compatible antihypertensive (usually labetalol). Notify your obstetrician right away for close monitoring of fetal renal function and amniotic fluid.

Are there any circumstances where ACE inhibitors are allowed in pregnancy?

No. All major societies-ACOG, AHA, EMA, Medsafe-state they are contraindicated in every trimester. Exceptions only exist in experimental settings under strict research protocols, which are extremely rare.

How quickly can blood pressure be stabilized after switching meds?

Most patients achieve target <140/90 mmHg within 3-5 days of initiating labetalol or methyldopa, provided dosing is titrated promptly and adherence is good.

Do these safe alternatives cross the placenta?

Yes, they do cross, but extensive research shows they have low toxicity and no consistent pattern of birth defects. That’s why they earn Category B or C ratings.

Keeping the fetus safe means planning ahead, staying informed, and acting fast when pregnancy is confirmed. By swapping ACE inhibitors or ARBs for labetalol, methyldopa, or nifedipine, clinicians protect both mother and baby while still controlling blood pressure effectively.