How Malnutrition Leads to Rickets: Causes, Prevention & Treatment

Oct, 3 2025

Rickets Risk Assessment Tool

Child's Information

Risk Assessment Results

Quick Summary

- Rickets is a bone‑softening disease caused primarily by vitamin D, calcium, or phosphate shortages.

- Poor nutrition-especially low intake of vitamin D and calcium-drives these shortages.

- Infants, toddlers, and kids with limited sunlight are most vulnerable.

- Fortified foods, safe sun exposure, and targeted supplements can stop the disease in its tracks.

- Early detection and treatment restore healthy bone growth.

When a child’s bones soften, widen, or bend, doctors label the condition Rickets a disorder of impaired bone mineralization in growing children, usually linked to deficits in vitamin D, calcium, or phosphate. The link between malnutrition and rickets isn’t a mystery-without the right nutrients, the body can’t lay down the mineral matrix that keeps bones strong.

What Exactly Is Rickets?

Rickets mainly affects kids before their growth plates close. The disease shows up as loosened teeth, bowed legs, and a pectus carinatum (pigeon‑chest) shape. Laboratory tests typically reveal low serum calcium, low phosphate, and a high alkaline phosphatase level, all signs the skeleton is trying to compensate for missing minerals.

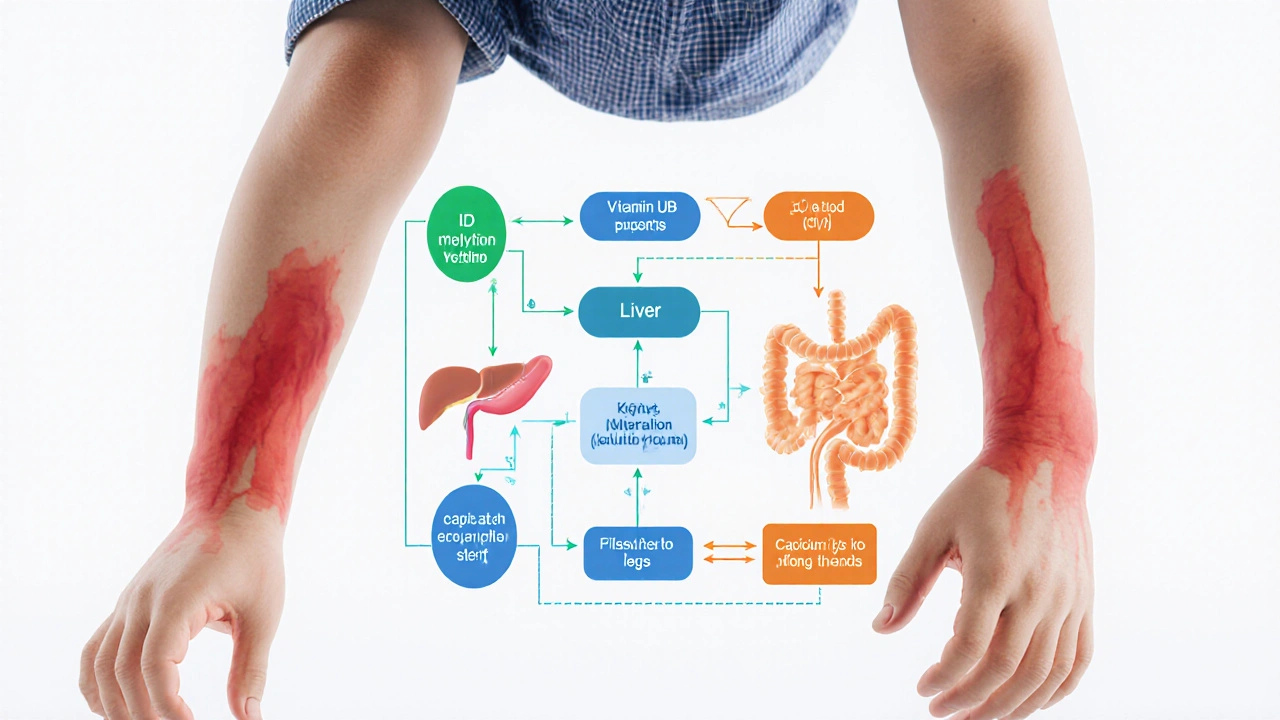

How Malnutrition Triggers Rickets

Malnutrition isn’t just “not enough food.” It’s an imbalance where essential micronutrients fall short. Three pathways dominate:

- Vitamin D deficiency - Without enough vitamin D, the gut can’t absorb calcium efficiently.

- Calcium deficiency - Even with adequate vitamin D, a diet low in calcium leaves the body scrambling for minerals.

- Phosphorus deficiency - Phosphate works hand‑in‑hand with calcium; a shortage skews the bone‑building chemistry.

When any of these nutrients dip, the body withdraws calcium from the bloodstream, leaching it from developing bones and causing the classic rickets symptoms.

Key Nutrients Involved

Understanding the main players helps spot the gaps in a child’s diet.

Vitamin D deficiency a condition where insufficient vitamin D limits calcium absorption from the intestines, often due to limited sunlight or poor dietary sources is the most common trigger. The skin synthesizes vitamin D when exposed to UVB rays; indoor lifestyles or high latitudes cut this natural production.

Calcium deficiency a shortage of calcium in the diet, affecting both bone mineralization and other cellular functions like muscle contraction can arise from diets high in processed foods and low in dairy or fortified alternatives.

Phosphorus deficiency an inadequate intake of phosphorus, which together with calcium forms hydroxyapatite, the main mineral component of bone is rarer but still relevant in regions where staple grains are heavily refined.

Other contributors include chronic diarrheal diseases that sap nutrients and genetic disorders that impair vitamin D metabolism.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Risk groups share common threads of limited nutrient intake and reduced sunlight.

- Infants exclusively breastfed beyond six months without vitamin D drops.

- Toddlers who consume mostly rice, noodles, or sugary snacks.

- Children living in high‑latitude areas (e.g., southern Australia during winter) where UVB is weak.

- Kids with darker skin tones who need longer sun exposure to produce the same vitamin D.

- Families facing food insecurity, leading to chronic malnutrition insufficient intake of essential nutrients needed for growth and health.

Prevention Strategies

Prevention combines nutrition, safe sun practices, and sometimes supplementation.

- Balanced diet: Include dairy (milk, cheese, yoghurt) or fortified plant‑based alternatives that provide at least 300mg of calcium per serving.

- Vitamin D sources: Fatty fish (salmon, sardines), egg yolks, and fortified cereals. In low‑sunlight months, a daily 400IU vitamin D supplement is recommended for infants and 600-800IU for older children.

- Sunlight exposure: Allow 10‑15minutes of mid‑morning sun, face and arms uncovered, 2‑3 times a week. Sunlight exposure UVB radiation that enables skin synthesis of vitamin D remains the cheapest, most natural source when done safely.

- Fortified foods: Look for milk, orange juice, or breakfast cereals labeled “fortified with vitamin D and calcium.” Fortified foods products enriched with vitamins or minerals to address common dietary gaps are a practical way to boost intake without altering meals.

- Breastfeeding support: Mothers who breastfeed should receive vitamin D drops (400IU/day) for themselves and the infant, especially in winter months. Breastfeeding the act of feeding a baby with breast milk, which can lack sufficient vitamin D without supplementation remains the gold standard for early nutrition, but supplementation fills the vitamin gap.

Treatment Options Once Rickets Is Diagnosed

Medical treatment focuses on correcting the specific deficiencies and monitoring bone healing.

- Vitamin D therapy: High‑dose oral vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol) - typically 2,000IU daily for 6‑8 weeks, then a maintenance dose.

- Calcium supplementation: 500‑1,000mg elemental calcium per day, divided into two doses, often as calcium carbonate or citrate.

- Phosphate management: In rare phosphate‑deficient cases, oral phosphate salts are added under physician supervision.

- Nutritional counseling: Registered dietitians create age‑appropriate meal plans rich in the missing nutrients.

- Follow‑up labs: Repeat serum calcium, phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase after 4‑6 weeks to confirm improvement.

Most children show radiographic improvement within months, and growth plates normalize once levels stabilize.

Practical Checklist for Parents

- Check your child’s diet: Does it include dairy or fortified alternatives daily?

- Track sun exposure: Aim for short, regular outdoor sessions, especially in spring and summer.

- Ask your pediatrician about a vitamin D supplement if your child is breastfed exclusively.

- Read food labels: Choose products fortified with both vitamin D and calcium.

- Schedule a bone health check if you notice bowing legs, delayed milestones, or frequent fractures.

Comparison of Key Deficiency Pathways

| Aspect | Vitamin D Deficiency | Calcium Deficiency |

|---|---|---|

| Primary cause | Insufficient UVB exposure or low dietary vitamin D | Low intake of dairy/fortified foods, high phosphorus load |

| Effect on gut | Reduced calcium absorption (≤30% of normal) | Normal absorption, but insufficient calcium available |

| Blood markers | Low 25‑OH vitamin D, low calcium, high PTH | Low calcium, normal vitamin D, elevated PTH |

| Treatment focus | Vitamin D supplementation + sun exposure | Calcium supplements + diet adjustment |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can rickets be reversed once it appears?

Yes. With proper vitamin D and calcium therapy, most children recover fully. Bone deformities may improve over six months to a year, especially if treatment starts early.

Why do breastfed babies need extra vitamin D?

Human milk contains very little vitamin D (≈25 IU/L). Without supplementation, an exclusively breastfed infant can quickly become deficient, especially in regions with limited sun.

Is sunlight enough to prevent rickets?

Sunlight is a powerful preventive tool, but factors like skin pigmentation, season, latitude, and sunscreen use affect synthesis. Combining safe sun time with diet or supplements offers the best protection.

What foods are naturally rich in calcium for kids?

Dairy products (milk, cheese, yoghurt), canned fish with bones (sardines, salmon), tofu set with calcium sulfate, leafy greens (collard greens, kale), and fortified plant milks are top sources.

How often should a child be screened for rickets?

Routine screening isn’t needed for well‑nutrished kids. However, if risk factors exist (e.g., exclusive breastfeeding without drops, limited sun, or signs of bone pain), a pediatrician should check serum calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D levels.