How Generic Substitution Laws Work: State-by-State Breakdown

Jan, 16 2026

Every year, Americans save billions of dollars because pharmacists swap brand-name drugs for cheaper generics. But here’s the catch: whether that swap happens at all depends on which state you live in. One state might force the substitution. Another might require your signature. A third might not let you know it even happened. There’s no national rule - just 51 different systems, each with its own maze of requirements.

What Exactly Is Generic Substitution?

Generic substitution means a pharmacist gives you a cheaper version of a drug that’s chemically identical to the brand-name version your doctor prescribed. The FDA says these generics work the same way, have the same side effects, and are just as safe. But the law doesn’t always let pharmacists make that switch on their own.

Back in the 1970s, most states required pharmacists to give you exactly what the doctor wrote on the prescription - no exceptions. That changed when states realized they were spending way too much on prescriptions. Louisiana led the way in 1980, letting pharmacists substitute generics unless the doctor said "do not substitute." Today, every state and Washington, D.C. has some version of this law.

The key tool? The FDA’s Orange Book. It lists which generics are officially rated as therapeutically equivalent to brand-name drugs. If a generic is in there, it’s legally eligible for substitution - but whether it gets substituted? That’s up to your state.

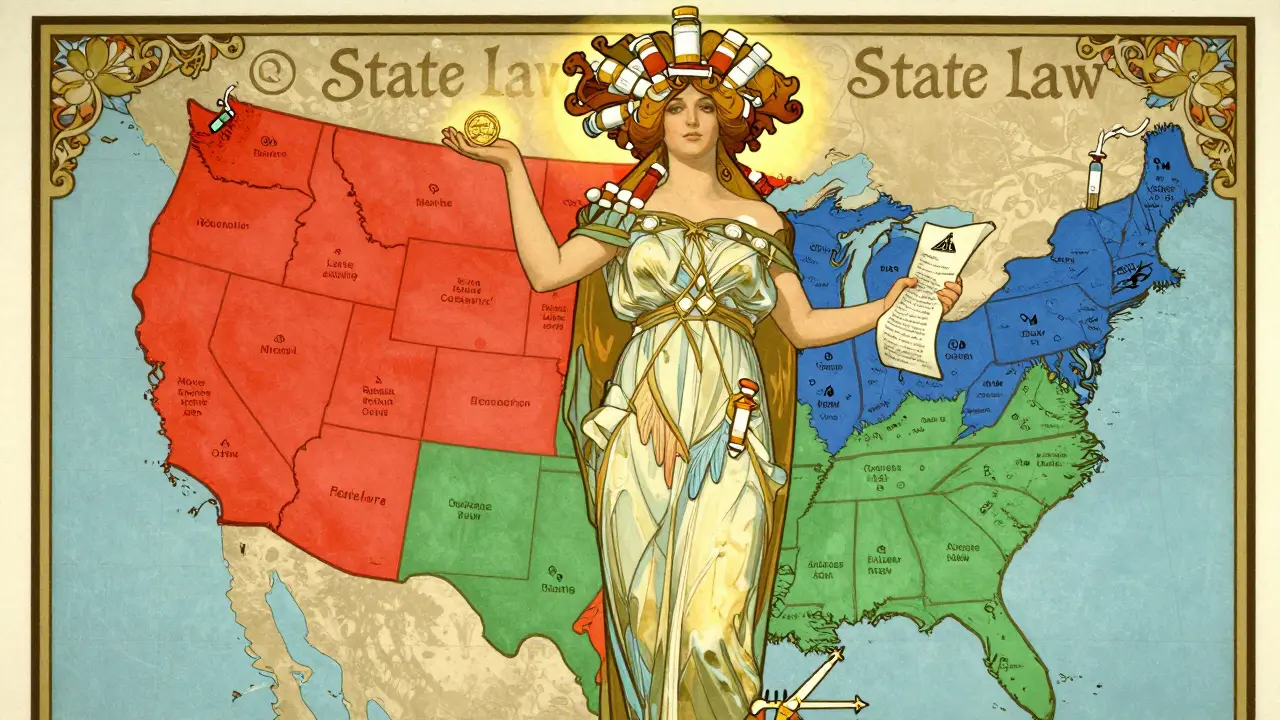

States That Force Substitution

Nineteen states - including California, New York, and Texas - have what’s called a "mandatory substitution" law. That means if a generic is available and the prescription doesn’t say "do not substitute," the pharmacist must give you the cheaper version. No asking. No waiting. Just save money.

These states assume that if the FDA says two drugs are equivalent, then the pharmacist can safely swap them. And it works: studies show generic use in these states is 8-12% higher than in states with permissive laws. That translates to $50-$150 saved per prescription, on average.

But even here, there are exceptions. Some drugs are too risky to swap. Kentucky, for example, bans substitution for drugs like warfarin and levothyroxine because tiny changes in dosage can cause serious problems. Same with certain seizure meds - in Hawaii, you need both your doctor’s and your own permission to switch an antiepileptic drug.

States That Let Pharmacists Choose

Thirty-one states and D.C. let pharmacists substitute generics, but they don’t have to. They can give you the brand name if they want - even if a cheaper generic is sitting right there.

That sounds like flexibility. But in practice, it creates confusion. Pharmacists in multi-state chains say they spend hours checking rules every time they fill a prescription for someone who lives near a border. One Walgreens pharmacist on Reddit said it’s a "nightmare for workflow efficiency."

In these states, substitution often depends on the pharmacy’s policy, the pharmacist’s comfort level, or whether the patient asks for the generic. That means two people with identical prescriptions might get different results - just because they walked into different stores.

Consent Rules: Do You Get a Say?

Here’s where it gets personal. Seven states - Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, New Hampshire, Vermont, and West Virginia - plus D.C., require you to give explicit consent before a generic can be given. That means the pharmacist has to ask you, "Do you want the cheaper version?" and you have to say yes.

Why? Because some patients, especially those on narrow therapeutic index drugs, worry that even tiny differences might affect them. The American Epilepsy Society pushed for these rules after reports of seizures linked to generic switches.

But here’s the twist: 31 states and D.C. don’t require your permission - but they do require you to be notified after the fact. You might walk out with a generic, and then get a notice on your receipt or in your prescription bag saying, "This drug was substituted." No chance to say no. Just a heads-up after the fact.

And in Oklahoma? The law says you can’t substitute unless the prescriber or the payer (like your insurance) says it’s okay. That puts the power in the hands of doctors or insurers, not pharmacists or patients.

Liability: Who Gets Blamed If Something Goes Wrong?

Pharmacists are caught in the middle. If they substitute and something bad happens, could they be sued? In 24 states - including Alabama, Arizona, Illinois, and Oregon - there’s no legal protection for pharmacists who switch to a generic. That means they could be held responsible if the drug doesn’t work as expected, even if it’s FDA-approved.

That fear leads to hesitation. A 2022 study found that in states without liability protection, pharmacists were more likely to stick with brand-name drugs, even when generics were available. Patients in those states often don’t realize their meds were never switched - they just think their insurance didn’t cover the generic.

Biologics and Biosimilars: The New Frontier

Biologics - complex drugs made from living cells - are the next big thing in high-cost meds. Think insulin, rheumatoid arthritis drugs, and cancer treatments. Their cheaper versions are called biosimilars.

But here’s the catch: 45 states treat biosimilars much more strictly than regular generics. Even if the FDA says a biosimilar is "interchangeable," pharmacists in many states still can’t swap it without the doctor’s permission.

And in six states - Florida, Indiana, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee - pharmacists can substitute generics but can’t substitute biosimilars without extra steps. That’s why, even though biosimilars are approved and cheaper, they make up only 11.2% of biologic prescriptions as of mid-2023.

Most states require pharmacists to notify the prescribing doctor within 2-7 days if they switch a biologic. But a 2022 survey by the National Psoriasis Foundation found that 42% of patients didn’t even know their biologic had been swapped. Notification rules exist - but they’re not always clear or followed.

What’s Changing in 2024?

States are starting to notice the mess. Twenty-seven states are currently reviewing or rewriting their substitution laws. The big push? Standardization.

In 2023, 12 states introduced the "State Harmonization of Generic Substitution Act," a model law designed to create consistent rules across state lines. It would require notification after substitution, eliminate consent for most drugs, and protect pharmacists from liability if they follow FDA guidelines.

The FDA also updated its Orange Book in 2022 to include new "interchangeability" ratings for complex generics. Eighteen states have already started revising their rules to match.

And the numbers speak for themselves. A 2023 study in Health Affairs found that states that simplified their laws saw generic use jump by 6.8% - and by 11.2% in states that removed patient consent requirements.

What This Means for You

If you take a generic drug, you’re probably saving money. But if you’ve ever wondered why your prescription changed - or didn’t change - when you moved, or switched pharmacies, now you know why.

Here’s what you can do:

- Always check your receipt or prescription bag for a substitution notice.

- If you’re on a drug with a narrow therapeutic index (like warfarin, levothyroxine, or seizure meds), ask your pharmacist: "Was this switched? Is it safe?"

- If your doctor wrote "do not substitute," make sure the pharmacy honors it - and keep a copy of the prescription.

- Call your state’s Board of Pharmacy if you’re unsure about your rights. They have free guides online.

Most people don’t realize that a pharmacy law in their state could be costing them hundreds a year. But now you do. And knowing the rules is the first step to making sure you’re getting the best - and cheapest - care possible.

How to Find Your State’s Rules

You don’t need to guess. The National Association of Boards of Pharmacy has an interactive map that shows exactly what your state requires. Just search for "NABP Substitution Law Map" - it’s updated every quarter.

Also, the FDA’s Orange Book app lets you check if a generic is approved for substitution. Type in the brand name, and it tells you which generics are rated "AB" - meaning they’re interchangeable.

And if you’re in a state that requires consent? Ask for it. Don’t assume. Your health - and your wallet - depend on it.

Can a pharmacist substitute a generic without telling me?

In 31 states and Washington, D.C., pharmacists must notify you after substituting a generic - but they don’t need your permission. In seven states plus D.C., they must get your explicit consent before making the switch. In Oklahoma, substitution requires approval from either your doctor or your insurer. Always check your prescription label or receipt for a substitution notice.

Why can’t I get a generic for my seizure medication?

Some drugs, like antiepileptics, have a narrow therapeutic index - meaning even small differences in how your body absorbs the drug can cause seizures or side effects. States like Hawaii and Kentucky ban substitution for these drugs unless both your doctor and you give written consent. The FDA still considers them therapeutically equivalent, but the medical community prefers caution.

Does my insurance force me to take a generic?

Medicaid programs in 42 states require generic substitution and charge lower copays for generics. Many commercial insurers do too - but they can’t override state law. If your state doesn’t allow substitution, your insurance can’t force it. However, if substitution is allowed, your insurer may refuse to cover the brand-name version unless your doctor says it’s medically necessary.

Are biosimilars the same as generics?

No. Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs, like aspirin or metformin. Biosimilars are similar - but not identical - copies of complex biologic drugs, like insulin or Humira. The FDA requires extra testing for biosimilars to prove they’re safe and effective. Even then, most states treat them more strictly than generics and require doctor approval before substitution.

What should I do if I think my drug was switched without my knowledge?

First, check your prescription label or receipt - it should say if a substitution occurred. If it didn’t and you’re in a state that requires notification, contact your pharmacist. If you notice new side effects or reduced effectiveness after a switch, talk to your doctor. You can also file a complaint with your state’s Board of Pharmacy. They track substitution complaints and can investigate if rules were broken.