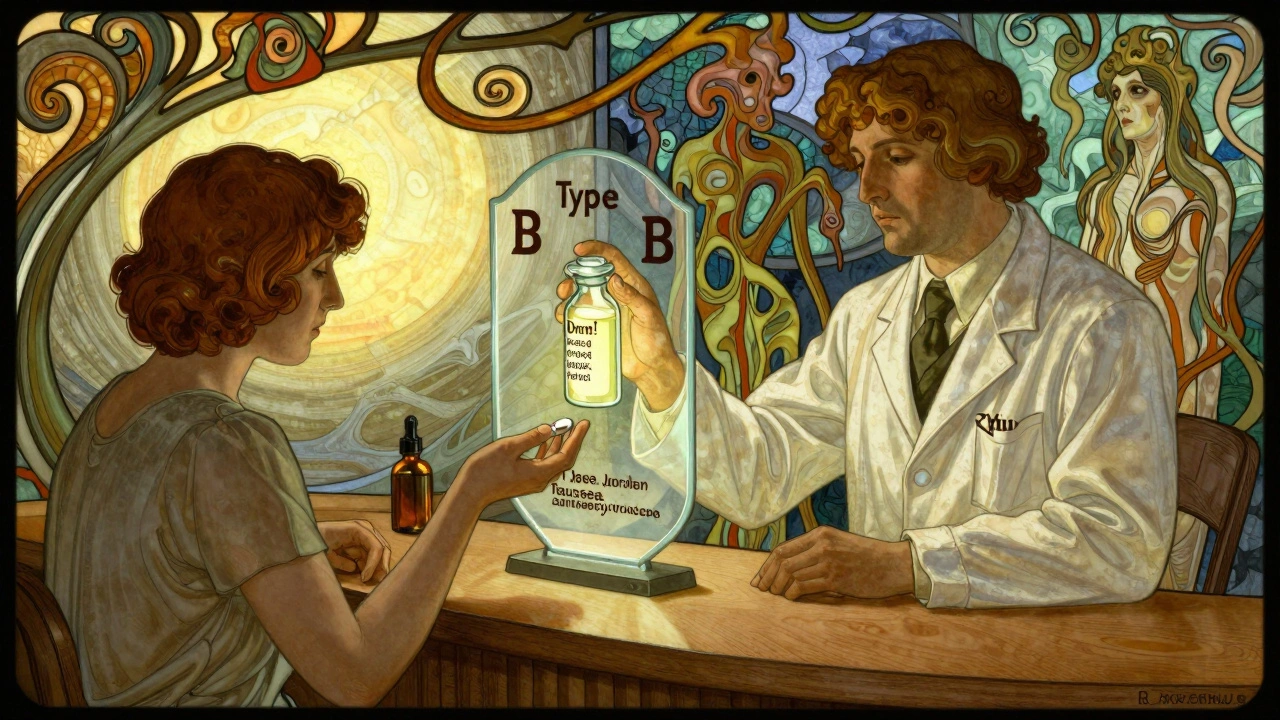

Type A vs Type B Adverse Drug Reactions: What You Need to Know

Dec, 1 2025

Adverse Drug Reaction Classifier

This interactive tool helps you understand whether a drug reaction is likely Type A (predictable, dose-dependent) or Type B (unpredictable, idiosyncratic). Based on the information you provide about the reaction, the tool will classify the reaction type and explain why.

Important: This is an educational tool only. For medical advice, always consult your healthcare provider.

Reaction Details

Reaction Classification

Key Characteristics

- Timing:

- Dose Relationship:

- Previous Reactions:

Most people assume that if a drug causes a bad reaction, it’s just bad luck. But the truth is, nearly all adverse drug reactions follow patterns - and understanding those patterns can save lives. About 85 to 90% of harmful reactions to medications aren’t random. They’re predictable, dose-dependent, and often avoidable. The other 10 to 15%? Those are the ones that come out of nowhere - no warning, no clear reason, and sometimes, no way to test for them ahead of time. This is where the Type A vs Type B classification system comes in. It’s not just textbook jargon. It’s the backbone of how doctors, pharmacists, and regulators decide what’s safe, what’s risky, and when to stop a drug before it’s too late.

What Are Type A Adverse Drug Reactions?

Type A reactions are the common, expected side effects. They happen because the drug is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do - just too much of it. Think of it like turning up the volume on a speaker until it cracks. The drug’s mechanism is amplified, not altered.

Examples are everywhere. Take NSAIDs like ibuprofen. They block inflammation, but they also reduce protective mucus in the stomach. That’s why 15 to 30% of people who take them regularly get stomach upset or ulcers. Or consider blood pressure meds. A beta-blocker slows the heart - great for hypertension, but if the dose is too high, it can cause dizziness, fatigue, or even a dangerously slow heartbeat in 10 to 20% of patients.

These reactions are dose-dependent. Double the dose? Double the risk. Half the dose? Often, the side effect fades. That’s why doctors start low and go slow. It’s not just caution - it’s science.

Type A reactions also include overdoses. Acetaminophen is safe at 4 grams a day. Go over that? Liver failure follows. Not because your body is weird. Because your liver can’t process the extra amount. Same with opioids: too much, and breathing slows. Too much, and it stops. These aren’t allergies. They’re pharmacological limits.

And here’s the kicker: Type A reactions make up most of the hospital admissions from medications. Not because they’re deadly - they’re usually not. But because they’re so common. A patient on warfarin gets a nosebleed because their INR is 6 instead of 2.5? That’s Type A. A diabetic gets low blood sugar because they took insulin and skipped lunch? Type A. These aren’t rare. They’re routine. And they’re preventable.

What Makes Type B Reactions So Dangerous?

Type B reactions are the opposite. They’re unpredictable. They don’t care about dose. They don’t care if you’ve taken the drug for years. One day, you’re fine. The next, you’re in the ER with a full-body rash, blistering skin, or a crashing immune system.

These are idiosyncratic - meaning they’re tied to your unique biology. Not your lifestyle. Not your dose. Your genes. Your immune system. Your liver enzymes. Something in you reacts to the drug like it’s a foreign invader.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome from sulfonamides? Type B. Anaphylaxis from penicillin? Type B. Malignant hyperthermia after anesthesia? Type B. These reactions occur in 1 in 1,000 to 1 in 100,000 people. They’re rare. But they’re deadly. About 25 to 30% of Type B reactions lead to hospitalization. Compare that to Type A, where only 5 to 10% do. That’s why Type B reactions are responsible for most drug withdrawals from the market.

Here’s what makes them so tricky: there’s no warning. No test. No way to know if you’re at risk - until it’s too late. That’s why doctors avoid prescribing certain drugs to people with known genetic risks. For example, carbamazepine can trigger a life-threatening skin reaction in people with the HLA-B*15:02 gene variant. That’s why in Southeast Asia, doctors test for this gene before prescribing. In the U.S., it’s less common - but it should be.

And here’s the twist: some reactions once thought to be Type B are now being reclassified. Thanks to pharmacogenomics, we’re finding that many “random” reactions have genetic roots. A 2023 study showed that nearly 40% of reactions labeled as Type B in the 1990s now have identifiable genetic markers. That means the line between “predictable” and “unpredictable” is blurring.

The Six-Type System: Why It Matters More Than You Think

The Type A and Type B system is useful. But it’s incomplete. That’s why experts use a six-type model - A through F - to capture the full picture.

Type C: Chronic effects from long-term use. Think steroid-induced osteoporosis or adrenal suppression after taking prednisone for more than three weeks. These aren’t sudden. They creep up. And they’re often missed because they look like aging or another disease.

Type D: Delayed reactions. The most chilling example? Diethylstilbestrol (DES). Given to pregnant women in the 1950s to prevent miscarriage, it caused a rare vaginal cancer in their daughters - decades later. One in 1,000 to 1 in 10,000 exposed daughters developed it. That’s Type D. A drug’s harm doesn’t end when you stop taking it.

Type E: Withdrawal effects. Stop opioids? 80 to 90% of dependent users get withdrawal within 12 to 30 hours. Stop antidepressants suddenly? Flu-like symptoms, brain zaps, anxiety. These aren’t relapses. They’re physiological dependence. Type E.

Type F: Therapeutic failure. This one’s sneaky. You’re taking birth control. You start rifampin for tuberculosis. The pill stops working. You get pregnant. Not because the pill is broken. Because rifampin speeds up how your body breaks it down. Type F isn’t a side effect. It’s a drug interaction that defeats the purpose.

These six types aren’t just academic. They’re used in 92% of European pharmacovigilance centers and in 78% of the 1.2 million adverse event reports filed with the FDA in 2022. They help regulators spot patterns. They help hospitals track risks. And they help doctors avoid repeating the same mistakes.

Immunological Classification: The Hidden Layer

When it comes to allergic or immune-driven reactions, the Type A/B system doesn’t go deep enough. That’s where Types I through IV come in.

Type I: IgE-mediated. Fast. Deadly. Anaphylaxis from penicillin. Happens in minutes. One in 2,000 to 5,000 courses. You know it when you see it: swelling, wheezing, drop in blood pressure. Epinephrine is the only fix.

Type II: Cytotoxic. Your immune system attacks your own cells. Penicillin can cause drug-induced hemolytic anemia - your body destroys your red blood cells. One in 8,000 to 10,000 courses. Lab tests show low hemoglobin and high bilirubin.

Type III: Immune complex. Drugs form clumps with antibodies. These clumps get stuck in tissues, causing inflammation. Cefaclor can cause serum sickness: fever, joint pain, rash. Seen in 0.05 to 0.1% of pediatric cases.

Type IV: Delayed cell-mediated. No antibodies. Just T-cells attacking. This is the classic maculopapular rash from amoxicillin. Appears 7 to 10 days after starting the drug. Looks like measles. Not life-threatening - but it’s common. Affects 5 to 10% of kids on amoxicillin. And it’s Type IV.

These four types explain why some reactions look nothing like typical side effects. They’re not about dose. They’re about your immune system’s memory. And they’re why you can’t just “try another antibiotic” after a rash. You might be setting yourself up for something worse.

Why Doctors Struggle to Classify Reactions

Here’s the reality: most doctors don’t classify reactions perfectly. A 2022 survey of over 1,200 physicians found that 78% found the Type A/B system “moderately useful” - but only if they had time to think about it.

Why? Because real life is messy. What if a patient gets a rash from amoxicillin - but only after taking 500mg three times a day for a week? Is that Type A (dose-related) or Type B (idiosyncratic)? A 2021 study showed serum levels of amoxicillin correlate with rash severity in some patients. That leans Type A. But other patients get the same rash on a tiny dose. That’s Type B.

And then there’s carbamazepine. It causes low sodium in about 20% of users. Is that Type A? It’s dose-dependent - higher doses = lower sodium. But not everyone gets it. Only those with certain kidney or hormone responses. So is it Type A? Type B? Both? Experts still debate it.

Even the FDA admits: about 15% of serious reactions don’t fit cleanly into A or B. They’re hybrids. That’s why newer systems are moving toward “mechanism-based” labeling - not just A or B, but “IgE-mediated,” “CYP2D6 poor metabolizer,” or “HLA-B*15:02 positive.”

And here’s the biggest challenge: mistaking a new disease for a drug reaction. A patient on statins develops muscle pain. Is it myopathy? Or just aging? A woman on antidepressants feels fatigued. Is it the drug? Or depression returning? 35 to 40% of complex cases are misclassified because the line between drug effect and disease progression is blurry.

What You Can Do: Practical Steps for Safer Medication Use

You don’t need to be a doctor to protect yourself. Here’s what works:

- Know your meds. Don’t just take the pill. Ask: “What’s this for? What side effects should I watch for?” If it’s a new drug, look up its most common reactions. Type A side effects are listed in the patient leaflet. Type B? Rarely mentioned.

- Track your symptoms. Keep a simple log: date, drug, dose, symptom. If you get a rash after starting a new antibiotic, note when it started. Was it day 3? Day 8? That helps tell Type A from Type B.

- Ask about genetic testing. If you’re being prescribed carbamazepine, abacavir, or certain cancer drugs, ask: “Is there a genetic test I should have first?” It’s not routine everywhere - but it should be.

- Don’t ignore withdrawal. Stopping antidepressants, benzodiazepines, or opioids cold turkey? You’re risking Type E reactions. Talk to your doctor about tapering.

- Report reactions. If you have a bad reaction, report it to your doctor - and to the FDA’s MedWatch program. Your report helps others. Over 1.2 million were filed in 2022. Yours could be the one that triggers a safety alert.

And remember: if a reaction happens after you’ve taken a drug for years, don’t assume it’s “just aging.” It might be Type D - a delayed effect. Or Type B - a new immune response. Either way, it needs attention.

The Future of Drug Safety

The future isn’t just about better labels. It’s about better prediction. By 2027, experts expect 60% of reactions currently called “Type B” to have known genetic triggers. That means instead of guessing, we’ll test. Instead of avoiding drugs, we’ll personalize them.

The World Health Organization is already testing AI tools that scan patient records to flag potential Type B reactions before they happen. The FDA is pushing for mandatory genetic screening for high-risk drugs. And the International Council for Harmonisation will roll out E20 Annex 2 in late 2025 - making the six-type system the global standard for reporting.

But here’s the bottom line: the Type A and Type B distinction isn’t going away. It’s too simple, too powerful. It’s the first thing every pharmacist learns. The first thing every nurse checks. The first thing every doctor asks when a patient says, “This drug made me sick.”

Understanding the difference isn’t about memorizing definitions. It’s about knowing when a reaction is a warning sign - and when it’s a red flag.

Because in medicine, not all side effects are created equal. And knowing the difference? That’s what keeps people alive.

What’s the difference between Type A and Type B adverse drug reactions?

Type A reactions are predictable, dose-dependent side effects caused by a drug’s normal pharmacological action - like stomach upset from NSAIDs or low blood pressure from blood pressure meds. Type B reactions are unpredictable, rare, and not related to dose. They’re often immune-mediated, like anaphylaxis or Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and can occur even with tiny amounts of the drug.

Are Type B reactions more dangerous than Type A?

Yes, in terms of severity. While Type A reactions are far more common (85-90% of all adverse reactions), Type B reactions account for about 30% of hospitalizations and are responsible for most drug withdrawals from the market. They’re rare - only 5-10% of reactions - but their mortality rate is 25-30%, compared to under 5% for Type A.

Can Type B reactions be predicted?

Traditionally, no - that’s why they’re called “idiosyncratic.” But advances in pharmacogenomics are changing that. Some Type B reactions, like carbamazepine-induced skin rash, are now known to be linked to specific genes (like HLA-B*15:02). Genetic testing before prescribing can prevent these reactions in high-risk people.

What are Type C, D, E, and F reactions?

Type C are chronic effects from long-term use, like osteoporosis from steroids. Type D are delayed reactions that appear months or years later, like cancer from DES exposure. Type E are withdrawal effects, like opioid or antidepressant withdrawal. Type F are therapeutic failures - when a drug stops working due to interactions, like birth control failing with rifampin.

Why do some people get a rash from amoxicillin and others don’t?

Amoxicillin rashes are often Type IV - a delayed, cell-mediated immune reaction. It’s not an allergy in the classic sense. It affects 5-10% of children and usually appears 7-10 days after starting the drug. It’s not dose-dependent, so even low doses can trigger it. It’s not dangerous for most, but it’s a sign your immune system reacted unpredictably - which is why doctors avoid re-prescribing amoxicillin after a rash.

Should I ask for genetic testing before taking new medications?

It’s worth asking - especially for drugs like carbamazepine, abacavir, or certain cancer treatments. Genetic testing can prevent life-threatening reactions. While it’s not standard for all medications yet, it’s becoming more common. If you’ve had a bad reaction to a drug before, or if your family has a history of adverse reactions, request a pharmacogenomic evaluation.